🌿 Are we beyond hope?

I sure hope so!

On this page...

Ahoy friends. In this museletter I tackle a theme that has come up in a few of the questions anonymously submitted by fellow readers (thank you). It seems that some of you are keen to hear this wizard’s perspective on ‘hope’. And so, at the risk of further distancing myself from the very lucrative world of professional hope-mongering, I shall share my stance. Be warned! I wax full philosophical here. Jolly feel-good listicles will return next week.

Are we beyond hope?

Gosh, I sure hope so!

The theme of ‘hope’ came up from a few questions I received since my last museletter to you. Here’s one such articulation:

2// if you do not really believe there is a polycrisis (as i do) and simply view much of the meta narratives as 'accumulations of fears' , isn't a fundamental principle of meaningful progress "unfearing"? the power of belief that anything tangled can be untangled (enough) to make progress?

3// isn't meaningful progress hopeful in nature? hope for something better (on a mesa and meta level)?

Thank you (all) again for the questions.

Here are some thoughts in response, delivered pell-mell.

1a// Quests err towards an optimistic disposition

There must be at least a simulacrum of optimism of stumbling upon a better way, or else: why bother. But the word ‘agnostimistic’ from The Lexicon of Lorecore is perhaps more apt.

Agnostimistic (adj.);

Neither optimistic nor pessimistic but a secret third thing.

Similar: Doom Mood Advantage.

Doom Mood Advantage (n.);

A competitive edge elicited by seeing the world not how it should be or could be, but rather as it actually is. Often confused with “Realism.”

Similar: Agnostimistic and Progress Paradox.

Progress Paradox (n.);

Confusion whether things are getting better but feel worse; or whether things are getting worse, but you feel better about it all. Solved by embracing Doom Mood Advantage.

1b// Purveyors of doom

In How to Lead a Quest I use the “The Inevitable Kraken of Doom” as a symbolic metaphor of fluidity and the existential threat of ‘irrelevance’ (which—like a kraken—often remains hidden until it is too late, and comes upon the becalmed who do not move or change—for only that which can change can continue). I’d say it’s less so ‘a common peril’ and more so a constant and pervasive threat in the everquest for relevance realisation. :D

2a// Fear the lack of fear

As someone whose academic foundation is in ecology and the science of living systems—I am inclined to believe that there is, indeed, a polycrisis and a metacrisis.

For those new to the terms, here’s what my AI intern came up with {lightly edited}:

‘Polycrisis’ refers to the concurrent and interlinked nature of multiple crises, like climate change, social inequality, political instability, and so on. The metacrisis expands on this by examining the conditions that perpetuate the polycrisis, with a particular focus on our (in)ability to adequately address the complex challenges we face due to fundamental flaws in how we think, govern, coordinate and act.

And so when you ask—isn't a fundamental principle of meaningful progress “unfearing”? the power of belief that anything tangled can be untangled (enough) to make progress?—my instinct is more aligned with Aragorn, Heir of Isildur.

Aragorn: “Are you frightened?”

Frodo: “Yes.”

Aragorn: “Not nearly frightened enough.”

I don’t think people quite have the appropriate level of fear, yet. The metacrisis is all a bit... abstract to most. Too cerebral. We humans are not good at comprehending exponentials at the best of times; let alone the compounding unknown unknowns of the complex living systems we are of. Eyes glaze over; or sharpen to fixate on specifics (removed from inter-relational context).

So I would thus be less inclined to reduce or ‘unfear’ folks. I fear that we (as a society) are already far too equipped and habituated to distract and numb ourselves to any hint of fear. We have streaming services, games, drugs, ‘ironic distance’, social media, online shopping—all the things to distract, enrage and delight us on the internet. The metacrisis can hardly compete for our attention; the slightest discomfort, bafflement or existential angst is readily usurped by a new cat video, or someone on the internet being wrong again.

But sometimes I wish the metacrisis could compete for our attention. I wish it were more visceral to those of us not already directly experiencing its effects. Not out of spite; more as a means of awakening more of us to what is happening—and being perpetuated—on our watch.

Thus, I’d be going less for ‘unfearing’ and more for ‘deepening the fear’—feeling it fully, and working through it as a means to transmute ourselves to better act on the other side of fear. If there is such a thing.

“Eco-anxiety researcher Panu Pihkala says that waking up to the climate and wider ecological crisis is particularly hard for middle-class citizens of industrialised nations because ‘the world is revealed to be much more tragic and fragile than people thought it was.’ This profound disruption, which can be as severe as an internal shattering, sends them into a grief-stricken process of mourning the lost future they believed would come a future of ecological stability. This then erodes their sense of security. As more and more people who’ve been living comfortable lives wake up feeling eco-anxious, that awareness comes with a risk. If we only turn inward, to recognise this pain within ourselves, instead of looking outward, to glean a sense of implication in the far-reaching and unequal consequences of the climate crisis and our agency to improve the outcomes, little will change. Better futures will be entirely missed if we get stuck in fear and dread.” from Generation Dread: Finding Purpose in an Age of Climate Crisis by Britt Wray (emphasis mine)

So: we can’t get stuck in fear and dread. But we also don’t want to deny, diminish or ‘unfear’, either. To simply use fear as a means to ‘raise awareness’ will likely be counter-productive—and not inspire generative thinking and planetary mutualism at higher orders of complexity. To quote from Venkatesh Rao’s Climate Posture:

And then there is of course the all-time-favorite: “Raising public awareness.” We’re well past useless diminishing returns on this front, and possibly into negative returns—public awareness can at most create a climate of temporary acute pressure on political processes. Pressure that is highly vulnerable to capture by misguided charismatic causes and unreliable messiahs. I suspect we’re at a stage in the evolution of the problem where more awareness means more people acting with urgency to secure their own futures at the expense of others’ futures.

It could be that by ‘unfear’ you are I are grasping at the same generative meaning. We both want folks to be appropriately post-fear, so that they are not acting in denial or irrational selfishness.

But I don’t even know if ‘fear’ is quite the right word for the metacrisis; perhaps ‘dread’, ‘despair’ and almost-but-not-quite ‘doom’ are more apt?

But these sensibilities are antagonistic to hope. More on this soon.

2b// Anything tangled kinda stays tangled

Regarding “the power of belief that anything tangled can be untangled (enough) to make progress”—yes, this is apt. But the thicket we make our way through is alive and writhing; whatever path we disentangle or hew will reform behind us anew.

In Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, scholar and cultural theorist Donna Haraway argues fundamentally against the idea of disentangling our entanglements. We are all inextricably linked; any disentanglement from this is a temporary (but sometimes useful) illusion. Lilypads of certainty.

Haraway argues for “making kin”—which is about acknowledging, respecting, and deepening our interdependencies, rather than attempting to extricate ourselves from them. For Haraway, the emphasis is on “response-ability”—the ability to respond to the complexities of our entanglements in a responsible and ethical manner. The goal is not to retreat into isolation but to form more equitable and sustainable relationships with the myriad entities with which we share our planet.

I like this. Translating it into a real practice is tricky to do within the context of modern society, but I am trying.

3a// Isn’t meaningful progress hopeful?

tl;dr – yes. Kinda.

But here’s where we get into the question of what meaningful progress is. It’s a question that has plagued me for years.

But in the context of the metacrisis, making profits and growing GDP seems like progress—but such activities accelerate and exacerbate the metacrisis.

To paraphrase Nate Hagens; in the modern world, we self-organise—as family units, small businesses, corporations, nation states, and as a global economic system—around profits. Profits are our goal, and lead to GDP globally. What we need for GDP is three things—energy, materials, and information. But we have outsourced the wisdom and the decision-making of this entire system to the market. We represent this by money, and money is a claim on energy. But the market is blind to the impacts of its growth. As a society we are drawing down the bank account of fossil fuels and non-renewable inputs like cobalt, copper, water aquifers, topsoil, forests—millions of times faster than they were sequestered.

And now to quote from Erin Remblance: “Energy use and material footprint are closely coupled with GDP and can’t be decoupled. Arguably they can’t be decoupled at all, but certainly not at the pace and scale necessary to achieve the science-based greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction targets without relying on speculative or problematic technology. We need to acknowledge the science: ‘green growth’ isn’t possible in the time we have available. Every time GDP goes up, we cause more environmental harm.”

Is it meaningful progress to grow a business if in so doing you further an omnicidal regime that is incentivising the degradation of life on the planet? In my perhaps more individualistic and naïvely hopeful past I would have had clever narratives to (genuinely) justify such, obfuscating my complicity. But nowadays I am all too aware of the entanglement. Thus, if ‘meaningful progress’ (to me) now means the flourishing of all life (not just human)—then I must question how we go about doing this when the rivalrous dynamics of this multipolar trap compels me to participate (and thus perpetuate) within the very system that’s antagonistic to the flourishing of all life.

There’s seemingly no escaping it, though. This wizard must still eat. I must also still pay my seneschal to tend to the moss that grows upon the southern aspect of my tower. And how would we feed the ravens that deliver these museletters to you, if not for the meta-optionality ‘claim-on-energy’ token we call money?

This is the quest I am personally on right now. And it’s not very fun. It’s a hellishly high-level quest, non-linear and fraught with existential peril, with no clear path. All objectives suspect. I long for the days before I had this insight-cascade; the epiphanic realisation that, shit, it really is bad. It was easier then.

Now, onto the notion of hope.

Northern and southern hemispheres tend to inverse the meanings of optimism and hope, I’ve found. Or we just lazily conflate the two. They are distinct, and there are nuances within hope itself.

Quest are hopeful in nature. But the hope is not centre stage; it’s a quiet reckoning we don’t allow ourselves to be fully allured by. Just as visions of utopia can be tyrannical, so too hope can seemingly bind us to a set path—blinding us to other possibilities. And, like an overly protective parent, hope can prevent us from having the experiences that lead us to new insight.

Friedrich Nietzsche said that hope is the worst of evils, “for it prolongs the torments” of those of us who hold to it. Arthur Schopenhauer, an existential philosopher, posits that hope muddles the rational understanding of events by equating the intensity of one’s desires with the likelihood of their fulfilment. Hope inevitably evokes it’s shadow—despair. (I’ve written about a similar phenomenon with regard to pride and shame). And Alan Watts has described ‘hope’ as being “the last evil in Pandora's box”, suggesting it might be a mechanism to keep humans subdued and complacent.

This is Professor Jem Bendell’s concern with hope, too. “Without talking to people, I believe we will be bulldozed back into denial by a media that tells us to be positive, hopeful and to carry on shopping and complying,” he writes in Breaking Together. He believes that “hope is acting as an escape from reality. For most people it involves wishing that something is not so. I am discovering I don’t need hope. Instead of hope, I have a sense of what is important to life, whatever may come.”

It’s been two over decades since I graduated as an environmental scientist and commenced my PhD research. In that time, I have seen little reversal of the trends that lead to ecological devastation and species loss, not to mention climate change and the myriad woes of the meta-crisis. In late 2019, when the bushfires ravaged parts of Australia—and I witnessed terrible scenes of burnt koalas (<— warning: sadness)—I felt immense despair. And then when I hear that logging is continuing to happen in critical habitat reserves for koalas (a now endangered species)... and then when I realise this is but one story for but one species... and when we realise that the current extinction rate is 1,000 to 10,000 times higher than the natural background extinction rate... it gets a little tricky to maintain ‘hope’ for our current path.

I know folks will say “it’s not too late”—and maybe I should read the book—but as Jem Bendell says: “When some of the people who speak publicly on existential risks tell us ‘It’s not too late,’ we should always ask: ‘It’s not too late for what and for whom?’”

What lies beyond hope?

Despair, perhaps. Depression, too. I’ve been there. Long-term subscribers will know that I am quite the fan of Professor Randolph Nesse’s theory of depression. Nesse and his colleagues speculate that depression could act as a biological constraint system that helps to minimise wasted effort and loss by forcing the individual to slow down, reassess, and potentially change strategies.*

* This is similar in how momentum inhibits reinvention. We also work with this concept in The ‘Choose One Word’ Ritual of Becoming, too.

But we don’t allow ourselves to get to this space because we consider depression so taboo. Chin up! You’ve gotta stay positive. There’s always hope.

There’s a phenomenon I experience, sometimes, when I am on a podcast or after I have given a keynote. There’s a sweet possibility space, potent with possibility. A space that is wondrously nebulous and ineffable, wherein we have a reawakened acuity for our inklings, glimmers, hunches and portents—the paths that otherwise remain occluded by narrow goals. This is the fertile precursor to quests.

But then the emcee or someone will say: “I feel like we have more questions than answers [as though this is a bad thing, ha]. What are three top tips or concrete, practical things we can do at work today or tomorrow to bring about <checks notes> meaningful progress?”

The attempt here is to collapse it into a neat linear step-by-step plan of obvious TODOs. I resist such, of course—the steps I suggest (like journaling, scheduling time, cultivating a questing fellowship, and so on) seem like concrete actions, but they are really just a means of preserving the possibility space.

Because that’s what lies beyond hope—despair, depression, acceptance, and then: new possibilities.

But we won’t get there if we cling to hope.

Daniel Schmachtenberger, a chap whom I have been quoting far too much these days, has had a profound run of appearances on various events and podcasts in the past few years. Recently—towards the end of a fantastic two hour interview on mental health in the metacrisis—he was asked: “is there one, maybe two things we can do, that is a little more hopeful of optimistic?”

I’ve linked to the timestamp in the video, but his initial answer was essentially to call out that it was a “goofy question”. And I love this moment; it gives me courage to call out the goofiness I see in the world. (He then proceeded to provide an elegant attempt). Goofy! Such an apt word.

I mean: I have hopes and dreams. I hope the barista will make my coffee at least as well as I can make at home. I dream of a world in which it is more economically viable to rehabilitate and protect life-sustaining ecologies than it is to destroy them. I also hope that my audiences and readers will have the time in this distraction economy to genuinely contemplate, question and consider worlds we live and work within. And I also dream of a time in which we see a renaissance in public intellectualism, where thinkers engage in generative dialogue not to ‘win’—but rather; to arrive at deeper understanding and new frontiers of knowledge and accord.

These are lovely hopes and dreams. But I also have Doom Mood Advantage, which enables me to see the world more as it actually is. And I don’t think I would have got there without the despair and depression that hope otherwise tries to shield and ‘protect’ us from.

“But how can we not leave everyone depressed?”

Again, Daniel Schmachtenberger—(and I swear, next museletter I will move onto other sources and a topic so light, flippant, obvious and affirming to counter all of this; brace yourself for some ‘top tips’ on how to ‘10x your productivity’ with ‘this one simple hack’)—ahem, again Daniel Schmachtenberger was asked, at the tail end of what I consider to be yet another profoundly heartfelt conversation about the metacrisis: “How can you not become depressed, if you really take this in?”

I’ve linked to the timestamp in the video (but I’d highly recommend the whole thing).

Suffice to say: Daniel did not take the bait and offer a predictable platitude. “I think people should let themselves become depressed... Either you’re actually an obligate sociopath that can’t feel shit,” Daniel says. “Or, you won’t let yourself because it’s overwhelming and you don’t know what to do with that... trust that. Let yourself go there anyways.”

Oooh, wait...

There is always something more to it. Truly.

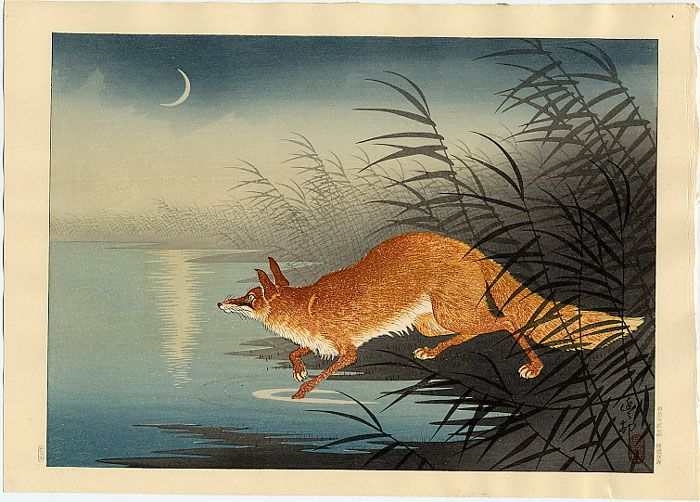

I used to talk of ‘beacons’—be they constellations or lights upon the distance—as sources by which we can navigate the complexities of life. But now there are no shining ‘obvious’ paths to me; only glimmers; distant foxfire and will o’ the wisps.

Yet, when we spend time in the dark, our eyes adjust—and new possibilities open.

I’ve been finding much solace within the pararational realms of the mythopoetic, as a balm to the otherwise clinical nihilism brought about by rationality alone. The mythologist Martin Shaw is one particular voice I find quite some resonance with.

In Courting the Wild Twin, he writes:

“Amongst the clear-eyed of us, hope is becoming a word laced with some doubt, and rightly so. At least from a certain point of departure. When I speak to the climatic conditions of our time through the voice of a pundit, philosopher, attender to the seemingly divinatory crackle of ‘the facts of the matter’, I feel a blue note of utter sorrow that I can’t come back from. But I do not choose to look at the conditions of our times only through those prisms; there is another, more ancient device. Story.”

When we attune to the mythopoetic—new possibilities and ways of seeing become available to us. Webs of relations reveal themselves, and everything teems with latent meaning. There’s a role that you and I and we can play in this.

Buster Benson writes eloquently on this.

“...we need new ways to address the perennial problems, and one of them that I see being most viable is to revive the mythic realm in a way that doesn’t challenge the strengths of the other realms. This will allow us to identify new salient possibilities (and motivations to act) via an epic story lens that are absent when we only try to address them with a scientific or economic lens, because solving these problems will never be cost-effective or practical in the moment.”

And so, in the pits of our despair—when all seems lost, remember: we are not (quite fully) doomed (yet). “When we prematurely claim doom we have walked out of the movie fifteen minutes early, and we posit dominion over the miraculous,” writes Martin Shaw. “We could weave our grief to something more powerful than that. Possibility.”

fin

Come hang with me at Purpose Conference. I’ll be upbeat, I swear. 😅

50+ speakers, workshops, a careers fair, “the best after-conference party ever”. Join 1,000 others as we hear from world-class thinkers and industry leaders to interrogate what it means to be #purposedriven in 2023. Museletter subscribers can receive a $100 discount with the code “JASONFOX” (that’s me). Tickets here.

Thank you so much for reading. Please feel free to comment or ask questions below; it is always lovely to hear from you. If you feel this might resonate with a friend, please forward it to them with a note that you appreciate them.

There’s more nuance I wish I could share on the matter of hope. In I Want a Better Catastrophe, Andrew Boyd does a great job of highlighting the notion of ‘grounded hope’. “Grounded hope offers us no guarantee that we’ll ever walk on out of the darkness, but it shows us how to walk through it. Here, one simply does what is right and what is necessary—and the doing and the walking are their own reward.” Anyways, I must wrap this up—I really ought be writing my next book for you. 😅

I remain, as ever, attuned to the glimmer that we may just somehow navigate our way out of this mess.

Much warmth,

—fw