🔮 Fourteen ‘must reads’ for those who lead

It’s dangerous to go alone – here, take any one of these books!

On this page...

If you’ve had the rare privilege and delight of having Dr. Fox work with you and your leadership team, you’ll know that I drop many book references. Especially during Q&A time, where richly complex questions deserve more than a pithy response. One of my roles is thus to play the part of a book-apothecarian. Tell me what vexes you and chances are I can prescribe to you a book written by someone who has thought on the matter quite deeply.

Having said that, there are a few sources I refer to quite frequently. These are useful in helping you develop the questing acuity, dispositional heuristics and poetic sensibilities necessary to lead meaningful progress amidst complexity, ambiguity and change.

1 // “How to talk about books you haven’t read” by Pierre Bayard

Firstly, a confession: I haven’t read this book. But I feel quite comfortable to talk about it. Mostly because it serves as a meta-point to this list, and that is—you ought approach books in a constellatory manner. And by this I mean: focus on where ideas are situated in relation to others. The relationships betwixt ideas are more important that the ideas themselves.

“As cultivated people know (and, to their misfortune, uncultivated people do not), culture is above all a matter of orientation. Being cultivated is a matter not of having read any book in particular, but of being able to find your bearings within books as a system, which requires you to know that they form a system and to be able to locate each element in relation to the others. The interior of the book is less important than its exterior, or, if you prefer, the interior of the book is its exterior, since what counts in a book is the books alongside it.”

The same applies to books.* Reading is—amongst other things—an activity in wayfinding. Thus: do not cling or adhere to any of the books I mention. As with complex systems, the relations are far more important than the nodes themselves.

* And, increasingly, The Internet—which means the ability to navigate memetic tribalism with enough ironic distance and requisite source-diversity so as not to become ensared by algorithmic capture; lest ye descend into intellectual echo-chambers and ideological cul de sacs.

2 // “Cynefin—weaving sense-making into the fabric of our world” by Dave Snowden and friends

The Cynefin Model of Complexity is an essential framework for leaders to know. Understanding the distinctions between complicated and complex contexts is paramount. Many leaders—having risen through the ranks of the system itself—fail to recognise complex contexts, and instead treat them as merely complicated. This often creates and/or perpetuates unintended consequences and harm.

“At its most basic, Cynefin allows us to distinguish between three different kinds of systems: ordered systems that are governed and constrained in such a way that cause and effect relationships are either clear or discoverable through analysis; complex systems where causal relationships are entangled and dynamic and the only way to understand the system is to interact; and chaotic systems where there are no effective constraints, turbulence prevails and immediate stabilizing action is required.”

Much of my work with leadership teams would be expedited if leaders had a deep knowing of complexity. I would add that Dave Snowden’s blog offers a trove of insight; see, for example, this list of principles for managing within complex systems.

3 // “Antifragile—things that gain from disorder” by Nassim Taleb

When asked to think of the opposite to that which is fragile, many respond with: tough, robust, resilient. But these qualities aren’t the opposite to fragility.

“Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better.”

Just as many leaders rely on their ability to drive results within complicated systems (rather than rise to the challenge of navigating complex systems), so too many leaders orient towards robustness over antifragility. This is inherently limiting, and the reason why so many successful organisations ultimately fail—robust systems are fragile to Black Swan events (that is: extreme impact events that are difficult to predict).

“Wind extinguishes a candle and energizes fire. Likewise with randomness, uncertainty, chaos: you want to use them, not hide from them. You want to be the fire and wish for the wind.”

Speaking of...

4 // “The Name of The Wind” by Patrick Rothfuss

I share this because leaders ought be avid readers. Or at least listeners* to rich and imaginative worlds outside of work.

* For podcasts, I highly recommend Poetry Unbound by Pádraig Ó Tuama.

The Name of The Wind is brilliant. Inadvertently, this book will help you navigate the mythopoetic realms of story, wisdom and truth.

“It's the questions we can't answer that teach us the most. They teach us how to think. If you give a man an answer, all he gains is a little fact. But give him a question and he'll look for his own answers.”

“All the truth in the world is held in stories,” Patrick writes. This is vitally important for leaders to understand—particularly the metric-obsessed. Especially so. Yet our path to gleaning this understanding is necessarily oblique.

“Using words to talk of words is like using a pencil to draw a picture of itself, on itself. Impossible. Confusing. Frustrating ... but there are other ways to understanding.”

Such a way is reading this book.

5 // “Finite and Infinite Games” by James P Carse

Just as many conventional leaders optimise for complicated systems in a robust manner, so too do they orientate toward finite games. This is tragically limiting.

You’ll probably see a pattern here. The conventional (domesticated) approach to leadership and leadership development is to groom operationally efficient agents within systems to continue to optimise for performance within the system itself. But what happens when the system itself needs to change?

“Finite players play within boundaries; infinite players play with boundaries.”

Something I love so much about this book is that it very much encourages a de-centering approach to leadership. Rather than seek to make ourselves the central nodes that everyone looks to and depends upon for the answers, we instead seek to make ourselves redundant. This is a paradox, I know. But all the best wisdom comes from paradox.

“Infinite play is inherently paradoxical, just as finite play is inherently contradictory. Because it is the purpose of infinite players to continue the play, they do not play for themselves.

The contradiction of finite play is that the players desire to bring play to an end for themselves. The paradox of infinite play is that the players desire to continue the play in others. The paradox is precisely that they play only when others go on with the game.

Infinite players play best when they become least necessary to the continuation of play. It is for this reason they play as mortals.

The joyfulness of infinite play, its laughter, lies in learning to start something we cannot finish.”

Just don’t make the mistake of buying Simon Sinek’s book “The Infinite Game”—a masterwork of bullshit wherein he managed to somehow both appropriate and misinterpret James P. Carse’s best ideas so that they could be reduced and repackaged into a mediocre business book. You deserve better.

6 // “Metarationality” and “Meaningness” by David Chapman

David Chapman has put together many deeply compelling thoughts into these hypertext books (along with Better Without AI, which is also very much worth reading—given all the hype and distortions that surround the field today*).

* David did his PhD in Artificial Intelligence, btw.

It is rare to find folks that can teach you how to think about thinking (without being prescriptive). But David Chapman has demonstrated an unrivalled aptitude for navigating the incredibly complex, nebulous and mercurial domains of meta-rationality (along with ethics and the fabric of meaningness itself).

Here’s the introduction to metarationality (aka learning to wield an invisible power):

“In fields requiring systematic, rational competence—science, engineering, business—some few people can do what may seem like magic.

They step into messy, complex, volatile situations and somehow transform them into routine, manageable problems. Textbook methods that were failing to come to grips with anomalies start working again.

Often these magicians have less relevant factual and conceptual knowledge than others who found the situation impossible. They may have no special skill in applying technical methods. Instead they may:

» Notice relevant factors that others overlooked

» Point out non-obvious gaps or friction between theory and reality

» Ask key questions no one had thought of

» Make new distinctions that suggest different conceptualizations of the situation

» Change the description of the problem so that different solution approaches appear

» Rethink the purpose of the work, and therefore technical priorities

» Realize that difficulties others struggled with can simply be ignored, or demoted in importance

» Apply concepts or methods from seemingly distant fields

» Combine multiple contradictory views, not as a synthesis, but as a productive patchwork.

They produce these insights by investigating the relationship between a system of technical rationality and its context. The context includes a specific situation in which rationality is applied, the purposes for which it is used, the social dynamics of its use, and other rational systems that might also be brought to bear. This work operates not within a system of technical rationality, but around, above, and then on the system.

This is meta-rationality.”

Useful, nay?

Around this time last year I leant on David Chapman’s work whilst unpacking The Labyrinths of Reason. If there was but one source to the secret of what I do (and attempt to teach), it would be David Chapman’s work coupled with the sensibilities from Finite and Infinite Games. Verily, this is all a must-read.

But it can be hard to know where to start. For enterprise leaders, I recommend the following:

» The Cofounders // An exploration of meta-systematicity in relationships, using the example of tech startup cofounders as they venture through to becoming a deliberately developmental organisation.

» What they don’t teach you at STEM school // “What they do teach you at STEM school is how to think and act within rational systems. What they mostly don’t teach you is how to evaluate, choose, combine, modify, discover, or create systems. Those skills are actually more important for social, cultural, and personal progress. Learning them is also rarer, and more difficult.” This piece does a wonderful job of scaffolding what a learning-journey toward meta-rationality.

» Developing ethical, social, and cognitive competence // Here David Chapman does homage to Robert Kegan—a pioneer in adult development research (and the co-author of the next book I recommend to you). This particular piece (from vividness—yet another collection of writing from David) is one of the earlier ones he wrote, and does an excellent job at positioning “the fluid mode” into the context of leadership, ethics and society—as links with this essay: A bridge to meta-rationality vs. civilizational collapse.

Anyhoo: that should get you started with David Chapman. Given the number of links I’ve just shared, may I offer this non-affiliate link to Readwise—the main app I use to save, read, highlight, annotate and collate that which I read. (I then have this synced to Obsidan, which allows me to export highlights so that I might literally ‘see’ the connections between ideas).

7 // “Immunity to Change” by Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey

Reading this book is like eating rye bread without butter. It’s dense and largely unexciting. But the key insights are worth it.

“To bring about significant change, people must come to understand the source of their own resistance to it.”

This resistance, the book reveals, is often due to hidden commitments and conflicting values. This creates paradoxical conundrums. We want you to innovate—but don’t you dare innovate is the implicit message of most enterprise leaders to their people. The tension here is the conflict between innovation and the status-quo (aka: change and stability).

If I were to crudely reduce the deftwork I do when serving as a facilitator-advisor to leadership teams, it would be to surface the conversation about conflicting values and make it explicit. This is what leadership offsites are for.

“The problem is that most people don’t really know what they believe. And they don’t necessarily believe what they think they believe.”*

* This reminds me of this passage from Daniel Khaneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow: “Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance.”

All good leaders have some level of mindful awareness as to their own thoughts. They do not bullshit themselves (or, at least, they are aware when they do). And they know that their “[...] current view of reality is just that—a view, not reality itself”.

This reminds me of the notion of “proto-synthesis”—something I gleaned from the next book.

8 // “The Listening Society” by Hanzi Frienacht

This is a psychoactive book, and not for the feeble-minded. A sample:

“[...] Over the years I have seen so much pain associated with wrestling the metamodern perspective. People get obsessed, they resist, they rage, they condemn, they belittle, they self-censor and find reasons to feel terribly affronted. I acknowledge that this is because my theories deeply insult the prevailing moral intuitions that people have. I spit straight in the face of their political identities, both on the Left and Right, from anarchists to conservatives. It is the solemn duty of the philosopher to piss on all that you hold dear and sacred, to show you that your gods are false.”

Metamodernism is a synthesis of the best elements of modernity and post-modernity. We see this in the arts, and also—as Hanzi Freinacht might put it—in our politics.

But I like to keep things apolitical, you might think. Sure. But remember: the apolitical stance is still a political stance. Someone benefits.

“Politics means games for power. Power matters in all aspects of life. Who makes the calls? Who is considered morally pure and sexy? Who gets to be smart and respectable, or to be the cool, romantic rebel? Who gets to be the kind, wise woman and who gets to be the boring old hag? Who gets the cards stacked against them in a fight they cannot win? What ideas rule the world and creep deep into our minds and dreams, constituting and structuring everyday reality? These, my friend, are the questions of politics in its true sense.”

As a leader you cannot afford to be blind to power and how it works. Additionally, you must develop the acuity to sense cultural shifts; to see around corners and glean what is emerging. And you must do so with both sincerity and irony. Sincerity alone does not work in the internet age—let alone the new era of deep fakery that AI will (continue to) unleash.

There’s so much I love about this book. The main thing I’d recommend from this book is the treatment it gives to the very perilous topic of adult development. Hanzi chooses Michael Common’s “Model of Hierarchical Complexity” as a framework for cognitive development (along with cultural code, state and depth); and I find it very compelling.

Again: I cannot overstate how dangerous this is (and how easily prone to misinterpretation can be). Yet still: this remains an immensely powerful framework—one that will assist any leader in navigating complexity in a manner that is deliberately developmental.

“I develop if you develop. Even if we don’t agree, we come closer to the truth if we create better dialogues and raise the standards for how we treat one another.”

This book is, however, very nordic. I love Scandinavia and The Nordic Ideology—but some ideas don’t quite translate. Particularly in an era of that is witnessing climate catastrophes, ecological collapse, the erosion of democracy, and the collapse of global “peace”. Development thrives in contexts that provide entropy and support. But right now, we are getting much more entropy than support.

As Professor Jem Bendell writes in Breaking Together:

“When we accept that modern societies are beginning to collapse, it can us lead to a critical view of the dominant systems and ideologies that produced this mess, distracted us from it, and channelled responses into decades of ineffective measures. That understanding means we begin to be liberated from the confines of respect for society-as-it-is.”

To be an actual leader in this chapter of humanity means we need to accept: we are now the adults in the room. This is not the time to delude ourselves. “When some of the people who speak publicly on existential risks tell us ‘It’s not too late,’” Jem writes, “we should always ask: ‘It’s not too late for what and for whom?’” Leadership, in this chapter, means venturing beyond hope.

It also means having an aspirational vision for what the future could look like. The Listening Society is one such vision, in what ought be a constellation of visions.

9 // “Sand Talk” by Tyson Yunkaporta

Beyond formal, systemic and meta-systemic thinking comes something much more paradigmatic and profound. Without the help of a good shaman, few of us have the opportunity to see the systems of our own thinking and being—let alone cross into a new paradigm. But Sand Talk by Dr. Tyson Yunkaporta does this, incredibly well. It’s like viewing Western society through the Indigenous perspective—you will never quite see things the same again.

“Civilisations are cultures that create cities, communities that consume everything around them and then themselves.”

I mean, I’ve played Civilisation and recommend it as a means to learn and access meta-systemic reasoning. But Tyson is right: the path is self-terminating—we shall consume the host, our planet, the very substrate we depend upon for life. Unless we course-correct.

Sand Talk offers sensibilities in how we relate to our role as custodial species—and this has direct implications for leadership. I’m at risk of overquoting the following—I literally used this line in my last post—but, bah. It’s potent.

“There is a pattern to the universe and everything in it, and there are knowledge systems and traditions that follow this pattern to maintain balance, to keep the temptations of narcissism in check. But recent traditions have emerged that break down creation systems like a virus, infecting complex patterns with artificial simplicity, exercising a civilising control over what some see as chaos. The Sumerians started it. The Romans perfected it. The Anglosphere inherited it. The world is now mired in it.”

Once you see life from outside the lens of the civilisation project—everything will have new context. Sand Talk also offers a glimpse of a hint of a way in which we can tend to and be amidst complexity. To orientate toward complexity, rather than against it.

Hoho, civilisational collapse aside, let’s return to lighter matters.

10 // “The Coaching Habit” by Michael Bungay Stanier

I’m a friend and fan of the author, MBS, and have had the delight of sharing the stage with him on quite a few occasions. All of MBS’s books are fabulous distillations, whittled to perfect aptness—The Coaching Habit is where I recommend leaders to start.

“If this were a haiku rather than a book, it would read:

Tell less and ask more.

Your advice is not as good

As you think it is.”

Ostensibly, the book promises to teach you how to effectively coach anyone in 10 minutes or less. It does this—but the reason I am sharing this with you is the core lesson: stay curious longer.

MBS introduces key questions in this book; the first two are my journaling prompts for every day.

The OMM question: what’s on my mind?

And the AWE question: and what else?

If you love questions (you should, at least as much as the protagonist in this comic)—you’ll love this book.

11 // “The Culture series” by Iain M Banks

Robin Sloan—whose newsletter and writing I highly, highly recommend (he’s a major inspiration to me)—wrote an insightful homage to the late Iain M Banks. The Culture is one of those space opera science fiction series that has a vision to aspire to. Right now, the future—through almost any lens—is bleak af. But—when reading any book from The Culture—you get a sense of what adult and societal development could look like in the far future.

Which, when you think about it, is actually quite rare. Most science-fiction films and books simply transplant today’s issues (mostly interpersonal and related to wealth/status/power imbalances) into the future. And then all the protagonists deal with these issues in the way they deal with them today (that is: immaturely; violently)—all to the back drop of a science-fiction aesthetic.*

* With the notable exception of Dune (and many other books from the golden era of science fiction). You should probably read Dune,° too, if you haven’t already. Yes the movie *is* brilliant, but the books are better. Well; at least the first book. Of course, it’s still got it’s White Saviour thing—it’s not perfect. But it’s okay.

° Actually, this quote from the first book that is very apt for leaders. “Greatness is a transitory experience. It is never consistent. It depends in part upon the myth-making imagination of humankind. The person who experiences greatness must have a feeling for the myth he is in. He must reflect what is projected upon him. And he must have a strong sense of the sardonic. This is what uncouples him from belief in his own pretensions. The sardonic is all that permits him to move within himself. Without this quality, even occasional greatness will destroy a man.” This is sincerity with ironic detachment and mythopoetic acuity, all at once.

In The Culture, though, you get to experience how an advanced society of post-humans handles complex challenges—with intelligence, wisdom and grace.

Also, don’t be turned off by the fact that Elon Musk purports to like The Culture series. A true fan would back concepts like this:

“Marain, the Culture’s quintessentially wonderful language (so the Culture will tell you), has, as any schoolkid knows, one personal pronoun to cover females, males, in-betweens, neuters, children, drones, Minds, other sentient machines, and every life-form capable of scraping together anything remotely resembling a nervous system and the rudiments of language (or a good excuse for not having either). Naturally, there are ways of specifying a person’s sex in Marain, but they’re not used in everyday conversation; in the archetypal language-as-moral-weapon-and-proud-of-it, the message is that it’s brains that matter, kids; gonads are hardly worth making a distinction over.” from The Player of Games

At the very least, if you seek to play the role of leader, read some science fiction for inspiration. Alongside fantasy, poetry and philosophy, too. Thx.

At this stage I best return to business books, ey?

12 // “Brave New Work” by Aaron Dignan

This book introduces “The OS Canvas”, which is—to our mutual delight—effectively a series of contextual containers for enquiry. The reason I am recommending it to you, dear reader, is because the questions proposed are exactly the kinds of questions enterprise leaders ought be keeping in mind.

How do we orient and steer? How do we share power and make decisions? How do we organize and team? How do we plan and prioritise? How do we invest our time and money? How do we learn and evolve? How do we divide and do the work? How do we convene and coordinate? How do we share and use data? How do we define and cultivate relationships? How do we grow and mature? How do we pay and provide?

I mean, just these questions alone are enough to set the agenda for many offsites and leadership development programs. I’ve referred clients to Aaron and his team—these guys are the real deal. Here’s an apt excerpt:

“We are addicted to the idea that the world can be predicted and controlled—that our stoplights are the only way to keep things in check. But when you view the world that way, today’s uncertainty and volatility become triggers for retreating to what has worked in the past. We just need to hire more capable leaders. We just need to squeeze out a little more efficiency and growth. We just need to reorganize... But we know better. The real barrier to progress in the twenty-first century is us.”

Aaron also runs a fab podcast along with Sam Spurlin—At Work with The Ready. Again, there’s a theme that runs throughout all of these recommendations: the future is not certain, and leaders cannot simply look back to what has worked in the recent-past. We need to be braver—or even: wiser.

13 // “The Wisdom of Insecurity” by Alan Watts

When presented with volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity and doubt—it’s natural to wish for stability, certainty, simplicity, clarity and conviction. But, wish as we may, leaders must meet reality as it is. There’s no pretending otherwise.

Of course, you might need to steward the narrative enough to create some lily pads of certainty—whilst knowing that these cannot be relied upon. Does this paradox vex you? Does it test your negative capability? Good. Paradox is both natural and the domain of leadership.

“We look for this security by fortifying and enclosing ourselves in innumerable ways. We want the protection of being ‘exclusive’ and ‘special,’ seeking to belong to the safest church, the best nation, the highest class, the right set, and the ‘nice’ people. These defences lead to divisions between us, and so to more insecurity demanding more defences. Of course it is all done in the sincere belief that we are trying to do the right things and live in the best way; but this, too, is a contradiction.”

Or, as Oliver Burkeman writes in The Antidote: happiness for people who can't stand positive thinking (another brilliant book, along with Four thousand weeks: time management for mortals): “We build castle walls to keep out the enemy, but it is the building of the walls that causes the enemy to spring into existence in the first place.”

I recommend leaders read The Wisdom of Insecurity if only that it may encourage them to soften their death-grip on stability, certainty, simplicity, and clarity. The drive to impose such things only exacerbates the need for them.

“To put it still more plainly, the desire for security and the feeling of insecurity are the same thing. To hold your breath is to lose your breath.”

The better you are able to embrace the wisdom of insecurity, the more effective you will be in navigating it.

14 // “Ribbonfarm” by Venkatesh Rao

This is a long-running blog (and newsletter) from one of the most refreshing thinkers on the planet. Not everyone can keep apace with with Venkatesh’s writing. But if you dive in it is worth the investment.

A classic from about seven years ago is this piece on why CEOs don’t steer.

“At the level of abstraction at which a CEO views what is going on, direction does not change, and more importantly, the CEO’s job is to make sure it doesn’t.

CEOs are orientation locks. The opposite of steering is orientation locking.

[...]

The primary CEO function, and the trait the good ones are selected for, is to provide the gyroscopic stability required to keep a company vectored in the chosen direction. They end up in the jobs they do because they counterbalance an organization’s natural tendency towards distraction, ADD and momentum dissipation. A typical company is a wandering, wobbling hive mind, liable to spend all its time chasing distractions if you let it, before dissolving into a bunch of clever tweets about crappy prototypes.”

Before this, Venkatesh was well known for The Gervais Principle. I’ve also loved The Art of Gig—parts one, two and three. The main reason I recommend this to you is that it provides yet another lens through which you can view enterprise leadership: the lens of an experienced (and sharp-witted) external consultant.

Last year Venkatesh co-authored a paper on The Unreasonable Sufficiency of Protocols. At first glance, this may not seem that significant, yet: in the decade I have been reading Venkatesh’s writing I’ve seen him remain very well positioned, ahead of the rest.

As a leader who cares about staying relevant, you would do well to collect a constellation of edge-thinkers via which you can cultivate your own (tentative) sense of what’s emerging.

Speaking of relevance...

bonus // “How to Lead a Quest” by Dr. Fox

It would be remiss of me to write nearly 5,000 words of book recommendations and not recommend my own work. How to Lead a Quest is “a handbook for pioneering leaders”. I wrote this for folks seeking meaningful progress amidst complexity, ambiguity and change. The book is written to be quite accessible, whereas my more recent hashtag quest leadership posts have dived a bit deeper. Essentially: questing is a precursor to strategy. We quest so that we can orient towards new and enduring relevance.

I also have The Game Changer—a book that explores motivation science and game design as a lens to influence motivation and behaviour. It’s more for team leaders than enterprise executives, and I wrote it a long time ago so... I am not sure how much I would recommend it now. 😅 Though many people still love it.

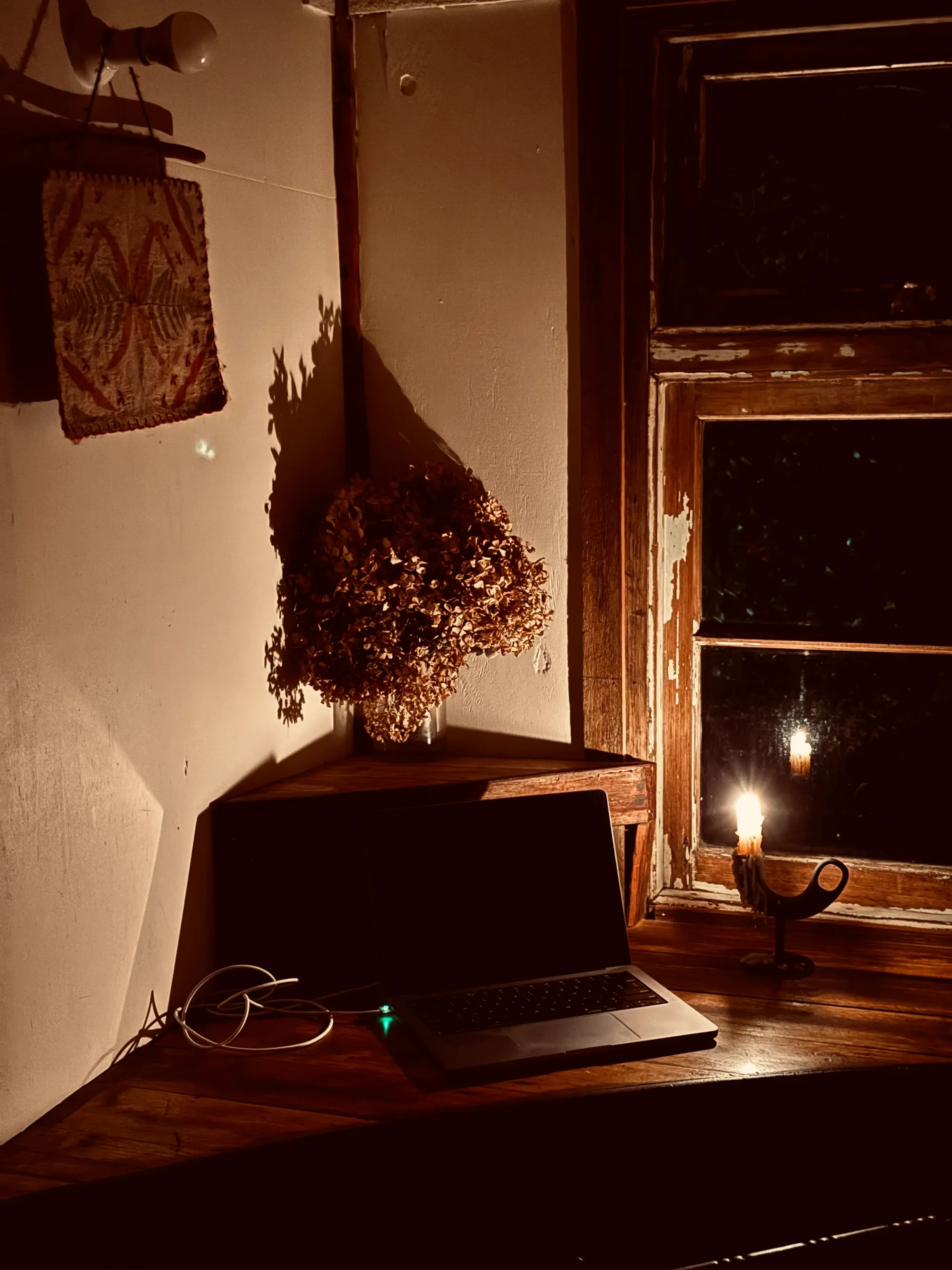

Finally, I have the book I am writing for you right now. I am currently on a writing retreat—in a tiny cabin by the woods—and this next book has been years in the making. This one weaves in elements from my The Ritual of Becoming—my online program to help you find and/or fabricate new motivation, meaning and myth in the next chapter of your life.

I’ll be sharing updates with subscribers as it unfurls. Meanwhile: here’s a photo of my context right now as I finish this writing list for you. I trust that these recommended reads will serve you well in the adventures ahead. ✦